Improvisation, notes on group walks

Walking accommodates. It’s something of a go-to form for socially engaged art, perhaps because extra people can easily come aboard. It is praised as an activity helpful for mind, body and soul. However this attractive approachability can pose a difficulty for those who plan group walks. Leaving the experience bare of a framework may feel too informal for organizers who have cultivated a particular audience, or those who desire to shape an art experience. On the other hand pumping in too much facilitation and programming in the structure of a walk can kill it, flatten it. The sense of meditation and awareness present while walking alone may suddenly become distant while in a group.

Setting a structure for each member of a group to enjoy the minute pleasures of a walk simultaneously can feel downright impossible for an organizer. There have been writers over the years who have argued that the true spirit of walking can only be found alone– or at least sans-conversation. It’s sometimes posed as an either/or equation. Either you have the discourse, or you have the reverie. However I’ve had a few experiences recently where a balance emerged between the two. This helped me see the group walk need not be thought of as a runner up in the experiential department. I should qualify– a group walk can easily be an intense social experience, bonding its members into a story. The question for me is more along the lines of “can a group walk retain a sense of personal meaning, as if it were itself an (art) object to be interpreted on an individual basis?”. My most recent experience of this sensation was on a thin twisting forest trail, again with family, my son taking the lead, I followed behind. I slowed my breathing to be able to hear better and I paid attention to the periphery of my sight. We were apart on the trail and conversation stopped. Each person seemed be in their own world, yet together at the same time. Then we re-engaged in conversation.

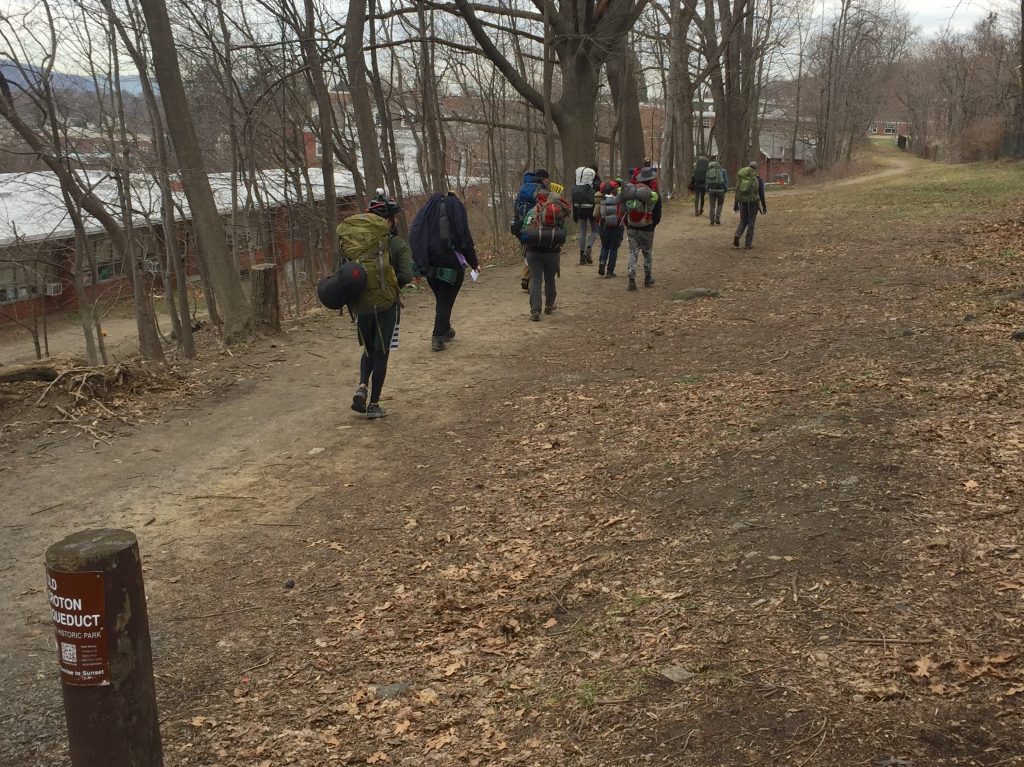

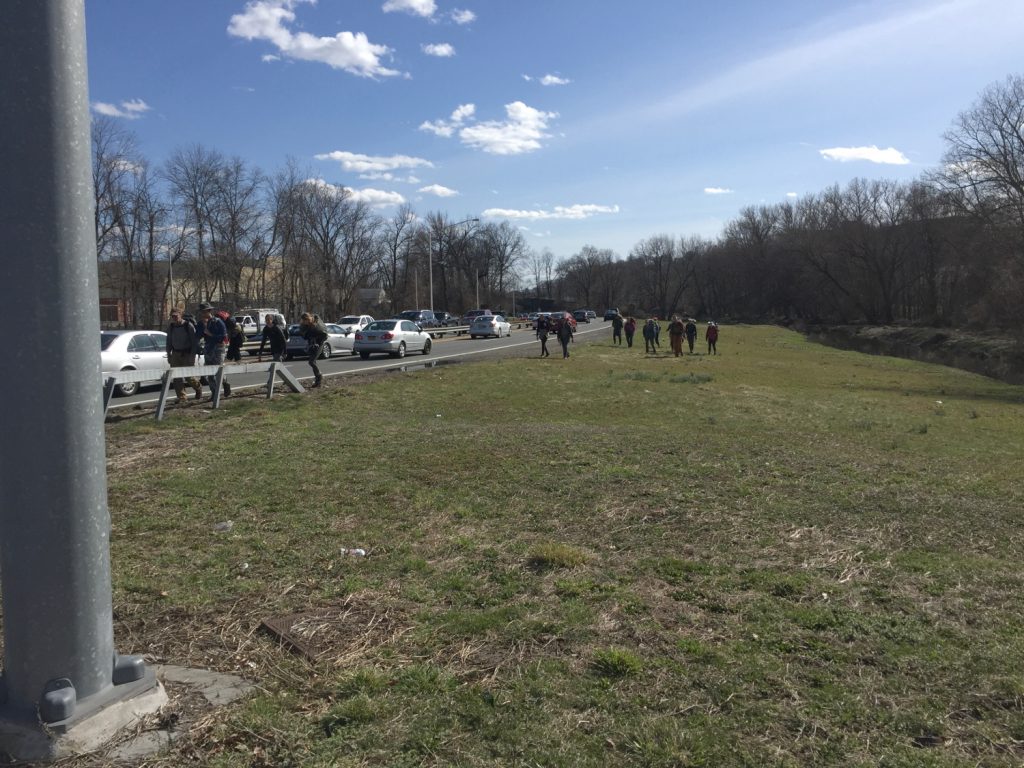

I’ve recently noticed two factors can help mediate a group-with-leader dynamic: the nature and existence of a trail, and the ability for each walker to improvise a personal flow between the various quotidian elements associated: breathing, moving, talking, seeing, listening, thinking. A trail, if it’s clear enough, allows for changes in leadership. I once led a silent walk in an area with a thin and inconsistent trail, at dusk. I decided to walk first, and a long line strung out behind me. At the end of the walk, one of the participants said it felt a bit “mother ducky”, which wasn’t necessarily meant as a jab, but stuck in my mind. The 2017 coyote walk consisted of 15 people walking for 3 days. The walk does not follow a single path, it changes between surfaces, roads and trails. This posed a challenge. I had never lead more than 10 people on a walk this involved and demanding. I had doubts about taking it on, but was eventually won over by the idea of embracing a larger solidarity possible with a larger group, especially in the light of a dismal political situation in the US.

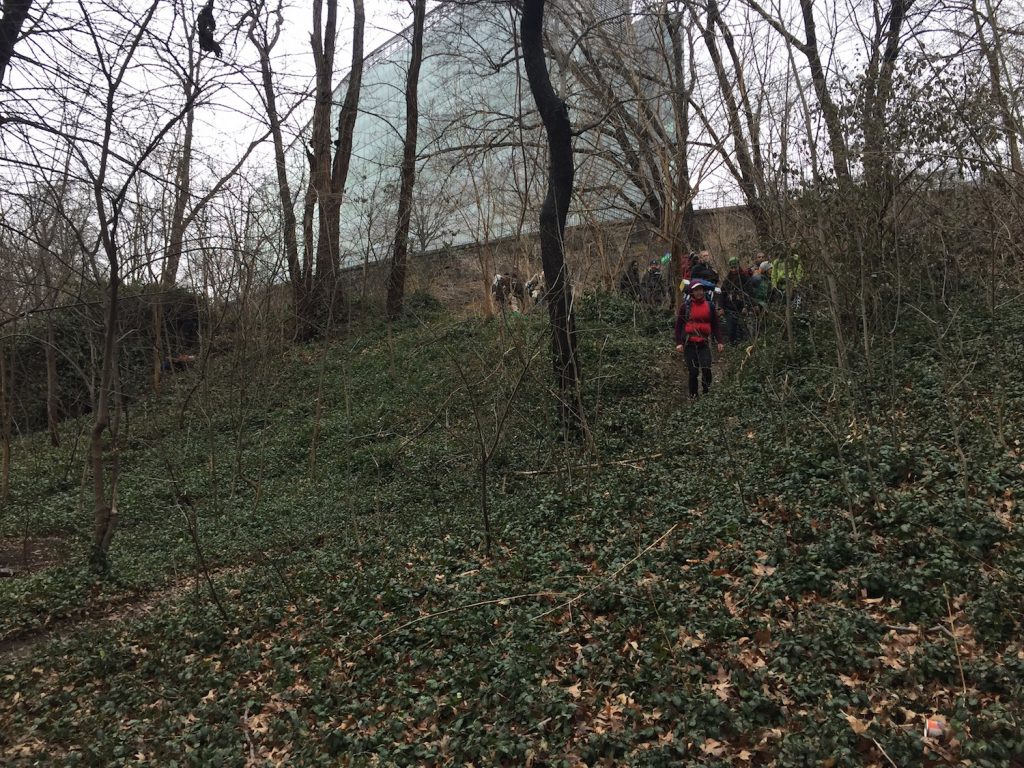

A few images for moments that I sensed (from my perspective) a balance took hold:

- Walking a neighborhood street we encounter a patch of forest running alongside homes. I know from overhead maps that we can cross the forested area to a bridge running over a highway. After briefly scouting and discovering that no path exists, the group fans out. One walker connects with a faint trail and becomes the group leader. Discussion is focussed on practical matters, then slowly picking through the brush in quiet.

- After a long road walk, connecting with a long, level, and wide dirt trail. Without cars. Walkers float forward and backward in arrangement seeing new faces, since there are few questions about navigation.

- A silent walking exercise arranged by a participant on the 3rd day of walking. Feeling tired enough to be relaxed and receptive for purely witnessing, among others.

- We split into two “teams” for half of a day, taking two routes to camp. Moments of leaving and meeting.

- Allowing for expanded stopping time, sitting by a stream.

There are ways of encouraging scenarios that might allow for each person to interpret and act within a walk, but I don’t think there is a prescription. I am still developing a sense for what they are. Many techniques (such as the simple act of stopping) are context specific, relying on a sense of listening, luck or even improvisation. I most enjoy moments when I am at liberty to make and take meaning in my walk and to share that experience– even if it can’t always be put into words– whether acting as leader or participant. I’ll step away from this walking residency now. I’ve tried to put a few thoughts on walking and talking, walking and remembering, walking and community. etc. in relation to the coyote project. Walking and writing, now that’s the hard one!