We always walk with technologies and we think of this as a kind of tinkering. Tinkering encourages serendipity which leads to unexpected outcomes. Some of our favourite examples of such outcomes are from medical science, such as the discovery of penicillin and the story of the frog and the spark. But of course, there are also many examples from the arts such as the tinkering of the Surrealists with the technology of photography (see the work of Lee Miller for example)

We think of the way we use technologies as ‘tinkering’ rather than ‘mixing’. Tinkering can be rearranging, repurposing, repairing, modifying and always involves familiarity with material at hand, embodied immersion and is deeply situated.

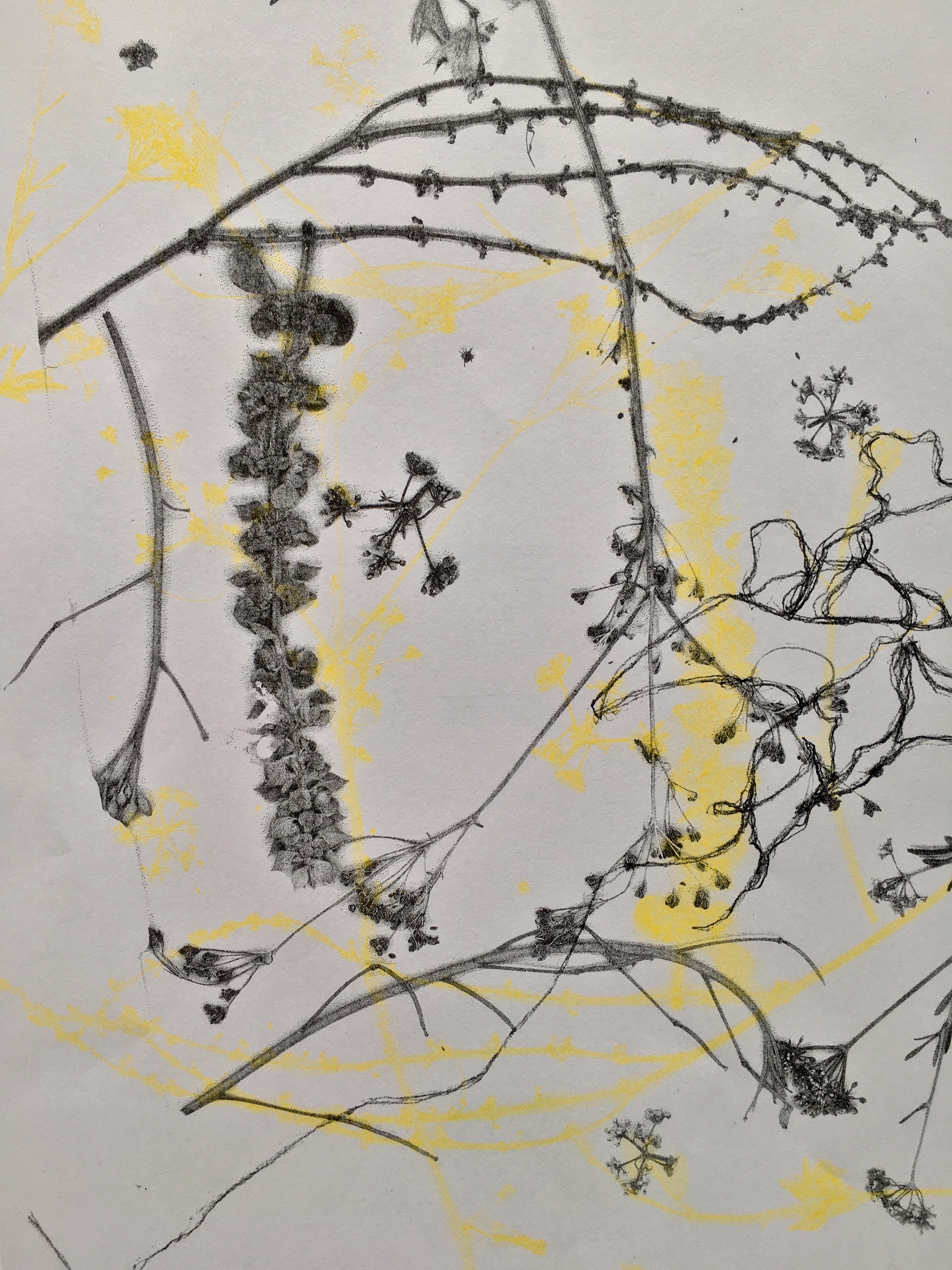

The appeal of tinkering is in its association to play. So rather than always seeing everything we are doing as part of a grand plan, sometimes we are literally playing at the edge of processes and technologies.

Playing with our smart phones is an important aspect of the way we walk.

Here are 2 ways we tinker with our phones that are free and readily available on our smart phones:

Map My Walk

We use Map My Walk. It is a simple app designed for tracking walking routes to ‘know where you’re going, see where you’ve been’ .

The app is part of the Map My Fitness suite of mobile apps and websites which the company claims is ‘building the world’s largest digital fitness community by providing interactive tools to make fitness social, simple and rewarding.’ We don’t engage with the core of the company, we just tinker at the edge.

This tool is an important tool for Mapping Edges because it helps to retrace our steps. On our seed ball walk we mapped our walk so that three weeks later, we could retrace and see which assemblages of seeds and edges have been successful in generating new edges.

Instagram

We use photography to frame what we are looking at, literally, and to record our observations. Instagram is used as a form of collaborative notetaking and a way to share our walks and our observations with each other.

How we observe, interact and tinker, is clear in our instagram feed.

We use as edges as a metaphor here by using the hashtag #mappingedges – we use other languages to find new edges. #kebun #giardino And we connect to gardening, permaculture, design, botanical and artist communities … and even car subcultures when we used the hash tag #drifting.